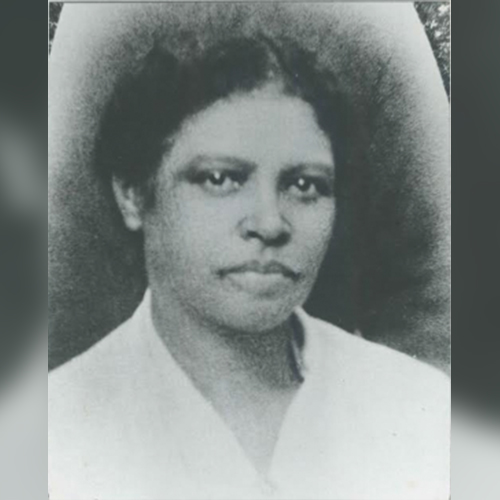

Mary Emma Townsend Seymour, a prominent 20th-century African American politician and union organizer, was born on May 10, 1873, to Jacob and Emma Townsend. Seymour was a political and social visionary whose activism, particularly on behalf of African American workers, laid the foundation for Black union organizing and civil rights activism in Hartford.Seymour’s beginnings were humble; she was the youngest of seven children and orphaned by the age of fifteen. Just before her mother’s passing in August 1888, she was adopted by Captain Lloyd G. Seymour, a distinguished Civil War hero and civil rights activist who served in the 29th Connecticut Volunteer Regiment. The Seymour family was one of Hartford’s most prominent African American families, and they inspired Mary’s appetite for community organizing. On June 3, 1888, she engaged in her first action when she entered the city’s Halls of Record at the intersection of Trumbull and Pearl Streets. At a time when Black women used naming to preserve their legacies, Seymour changed her birth name from “Mary Emma” to “Mary Emma Townsend Seymour.” Reclaiming her identity marked the beginning of her journey as a freedom fighter and champion for women.On December 16, 1891, Mary married Frederick Seymour, one of the first African American U.S. Postal Service workers in Hartford. A year later, the couple welcomed their first and only son, Richard, who died as an infant and buried at Old North Cemetery.By the turn of the 20th century, African Americans fleeing the Jim Crow South and immigrants from the Caribbean poured into the urban North, radically changing the complexion of Connecticut. The African American community swelled along Gold, Lewis, Hicks, and Pearl Streets. From the Hartford Fire Insurance Company to the Sisson Drug Company, African Americans worked as janitors, porters, waiters, chauffeurs, and domestic workers. In some cases, they owned their own barbershops, beauty salons, and funeral homes. Through the 1910s, Mary Seymour emerged as a civil rights activist, union organizer, and suffragist, forming interracial coalitions of activism committed to addressing unemployment, education, working conditions, racial segregation, poor housing, lynching, and disenfranchisement.Inspired by the 1917 anti-lynching rally in Hartford, Seymour, along with W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, founder and field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement for Colored People (NAACP), formed the first local chapter in Connecticut. On October 9, 1917, the Seymour hosted NAACP officers–Du Bois, Johnson, and Mary Ovington–at their home at 420 New Britain Avenue. They officially chartered the branch, alongside other leaders including the Reverend R. R. Ball of the A. M. E. Zion Church, Dr. Rockwell H. Potter, Dean of the Hartford Theological Seminary and a leading white reformer, and three white female reformers and suffragists: Mary Bulkeley, Josephine Bennett, and Katherine Beach Day. At the branch’s first meeting on November 26th, Mary Seymour became the branch’s administrative officer, a typical role for women in the NAACP.Like most African American women in Hartford, Seymour also formed and joined clubs and organizations that assisted African Americans fleeing the terror of the Jim Crow south. She joined the Colored Women’s League of Hartford, established in 1917 as a cornerstone institution servicing black women and children. In May 1918, she formed the local chapter of the Circle for Negro War Relief, Inc., which addressed the needs of soldiers of color and their families. Seymour highlighted the paradox of Black soldiers in her letters to the editor of the Hartford Courant and the NAACP’s Crisis. In a letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant dated July 2, 1918, Seymour addressed these challenges by stating:“They are not with their lot in this democracy, which is going forth to make the world safe for democracy. There are so many parts of this country that are not decent places for [Blacks] to live in – yet they are dying and going to die to ‘make the world a decent place to live.’ They have more to forget and forgive than any racial group beneath the Stars and Stripes.”During her time with the Circle for Negro War Relief, Seymour worked with several Connecticut suffragists such as Carolyn Ruutz-Rees, chairperson of the Women’s Committee of the Connecticut State Council of Defense, and produced a detailed report of how African American soldiers were discriminated against in the Army, Navy, and Red Cross.During the war, Seymour also championed workers’ rights for African Americans in Hartford. In addition to domestic work, Black women worked in warehouses stripping tobacco leaves while men labored in the fields. Seymour fought against the white foremen who cheated the women out of fair wages. Seymour, in collaboration with her friend, Josephine Bennett, formed the first all-Black women’s union in Connecticut. In addition, with Bennett, Seymour contacted the International Garment Workers Union, who sent a representative to assist in the organizing process. Seymour made her residence the union headquarters, and at its peak, the union had sixty-one African American women who were dues-paying, card-carrying members. Seymour and Bennett served as representatives of the state’s Central Labor Union, challenging deep-seated divisions along racial and gender lines. By the end of the war, Seymour evolved into one of Hartford’s leading voices, fighting against racial discrimination, lynching, labor discrimination, and disenfranchisement.Between 1917 to 1920, Seymour was among a handful of African American women in Connecticut who advocated specifically for voting rights for women. Despite her long commitment to suffrage, racial barriers prevented Seymour from joining the National Woman’s Party (NWP) and working with the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association (CWSA). At her recommendation, the NAACP petitioned Alice Paul and the NWP, but the white suffragists ignored their inquiries. While Seymour had a long-standing friendship with CWSA member Josephine Bennett, Seymour would fight for voting rights through the Farm-Labor Party whose platform included the nationalization of major industries, workers’ rights, a national anti-lynching bill, demilitarization, and the destruction of imperialism. In 1920, Seymour joined the first cohort of American women who ran for office after the passage of the 19th Amendment. She ran for the Hartford City Board of Education, and on the Farm-Labor ticket ran for state representative to the General Assembly. Historian Rosalyn Terborg-Penn described how Seymour belonged to a cohort of our nation’s first African American women candidates running for state office. While Seymour’s historic run has been well-documented, what is less known is her 1922 run for Connecticut’s Secretary of State, becoming the first African American woman to run for this state position.From 1920 onward, Seymour remained actively involved in the political landscape of Greater Hartford. In 1926, she resigned from the NAACP’s executive board and worked on behalf of Black workers until her death on January 12, 1957. Her legacy lives on in the Greater Hartford NAACP, Mary Seymour Place (formerly known as My Sister’s Place), and the hearts of all the activists fighting for freedom and equity.

Colored Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, October 21, 1917, RG012, State Archives, Connecticut State Library | From left to right, Elizabeth R. Morris, Mary A. Johnson, and Rosa J. Fisher

Colored Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, October 21, 1917, RG012, State Archives, Connecticut State Library | From left to right, Elizabeth R. Morris, Mary A. Johnson, and Rosa J. Fisher Colored Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, October 21, 1917, RG012, State Archives, Connecticut State Library | From left to right, Elizabeth R. Morris, Mary A. Johnson, and Rosa J. Fisher

Colored Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, October 21, 1917, RG012, State Archives, Connecticut State Library | From left to right, Elizabeth R. Morris, Mary A. Johnson, and Rosa J. Fisher Inspired by the words of notable African American reformer and political activist, Mary Townsend Seymour, “The work must be done,” the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History presents exciting new research about the women of color who worked for women’s suffrage. As the nation, and Connecticut, celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment which legalized women’s right to vote, attention is growing about the critical need to identify and raise up the stories of the women of color who participated in the fight for suffrage and those who, like their white counterparts, were against the enfranchisement of women. Historically, research about the fight to win the right to vote has focused on the white women who were both for and against this act. Due to the internalized racism of many of the national and state-wide suffrage organizations, women of color, and particularly African American women, were denied agency within these activist organizations. This does not mean that women of color were not involved in the fight for and against suffrage. They absolutely were. Women of color were active leaders who developed their own associations, both nationwide and state-based, to achieve social and political reforms, including working for woman suffrage.

Inspired by the words of notable African American reformer and political activist, Mary Townsend Seymour, “The work must be done,” the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History presents exciting new research about the women of color who worked for women’s suffrage. As the nation, and Connecticut, celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment which legalized women’s right to vote, attention is growing about the critical need to identify and raise up the stories of the women of color who participated in the fight for suffrage and those who, like their white counterparts, were against the enfranchisement of women. Historically, research about the fight to win the right to vote has focused on the white women who were both for and against this act. Due to the internalized racism of many of the national and state-wide suffrage organizations, women of color, and particularly African American women, were denied agency within these activist organizations. This does not mean that women of color were not involved in the fight for and against suffrage. They absolutely were. Women of color were active leaders who developed their own associations, both nationwide and state-based, to achieve social and political reforms, including working for woman suffrage.